The Effect of Party Cues in Real News

Invited for resubmission at

American Journal of Political Science

In democracies, news media have the vital task of informing the public about where political parties stand on policy issues. A large literature suggests that citizens respond to such information, known as party cues, by adopting the stances of their party. However, large party cue effects are found mostly in stylized experiments that use artificial vignettes or unusual issues, raising the question of whether party cues in actual news coverage hold similar sway. To explore this, I develop a new experimental paradigm. First, I sample 70 articles covering political proposals from a large population of real news. Then, working with a journalist, I prepare two versions of each article: one with and one without party cues. Finally, these articles serve as treatment material in two survey experiments among representative samples of 12,177 Americans. I find that party cues in real news have mostly modest effects on citizens’ policy opinions.

Link

Degrees of Disrespect: How Only Extreme and Rare Incivility Alienates the Base

The Journal of Politics, 84(3), 1746-1759.

When evaluating their own politicians, do partisans tolerate or punish the incivility now common in political discourse? While the answer is crucial to understand rising incivility, prior findings are mixed. I propose that copartisans tolerate milder degrees of incivility, which out-partisans punish, but that a limit exists beyond which the rhetoric becomes too extreme for even the base. Consequently, to examine whether copartisans tolerate or punish the incivility in current discourse, we must compare (1) how strong of an incivility they will tolerate to (2) how strong the incivility in current discourse is. To make this comparison, I develop a method integrating survey experiments with crowdsourced content analysis, which maps stimuli onto the distribution of online incivility among Congress members. I find that copartisans tolerate typical degrees of incivility, as the incivility in current discourse is rarely so extreme that favorability among copartisans drops. However, typical degrees lower out-party favorability, reinforcing polarization.

Dimensions of Elite Partisan Polarization: Disentangling the Effects of Incivility and Issue Polarization

British Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 1457-1474.

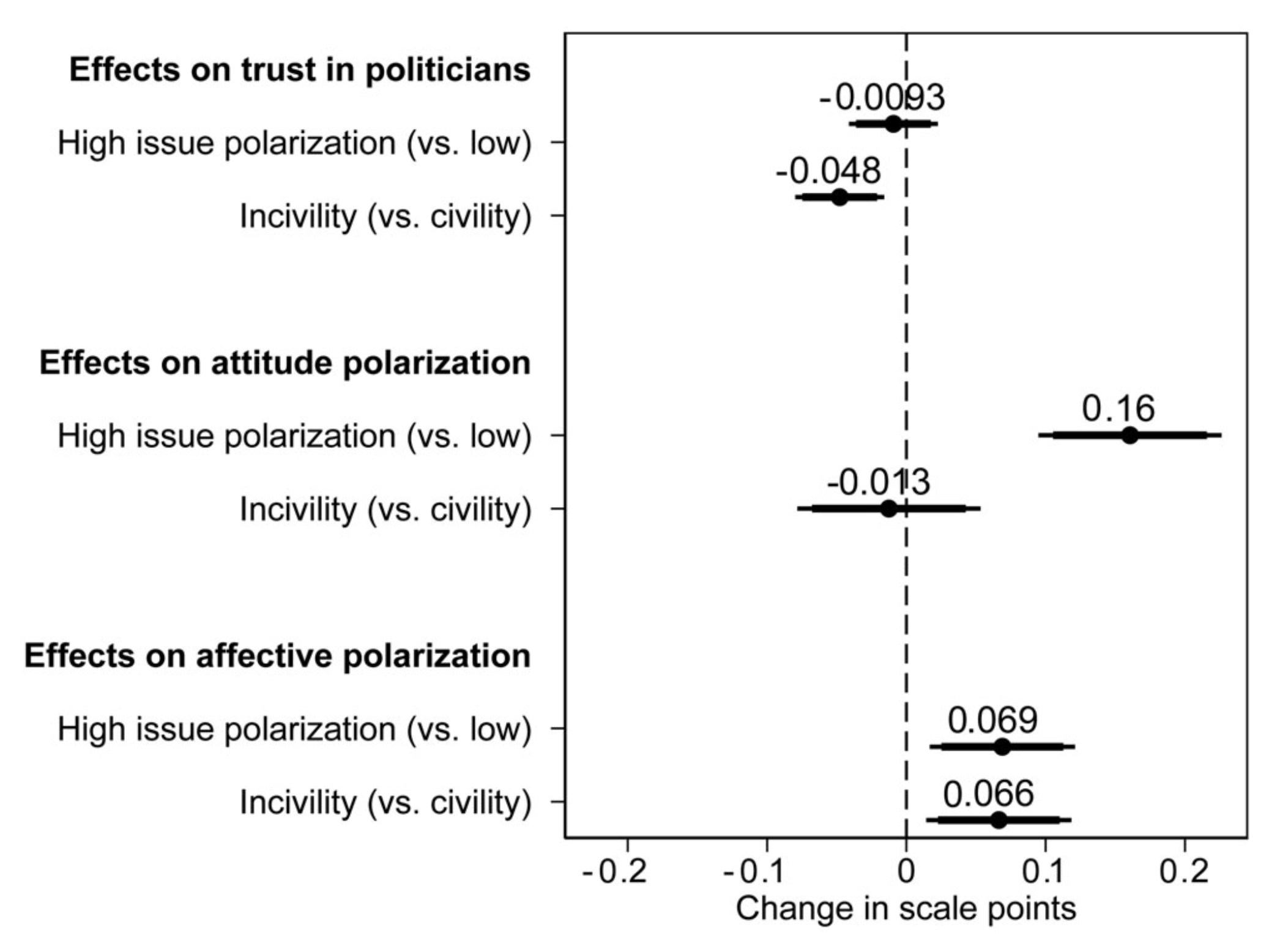

Elite partisan polarization has been found to have several potentially problematic effects on citizens, such as creating political distrust and different types of polarization among partisans. However, it remains unclear whether these effects are caused by the parties moving apart in terms of issue positions (issue polarization) or by the rise of disrespectful rhetoric (incivility). In the literature, these two dimensions of elite polarization often appear to affect citizens in similar ways, but typical research designs have not been well suited to disentangling their effects. To determine their unique effects, four studies have been conducted using original designs and a mix of experimental and observational data. The results show that issue polarization and incivility have clearly distinct effects. A more uncivil tone lowers political trust, but increasing issue polarization does not. Conversely, only issue polarization creates attitude polarization among partisans. Both aspects of elite polarization create affective polarization.

Link

Self-Affirmation and Identity-Driven Political Behavior

APSA award winner: Rebecca Morton Best Paper in JEPS Award 2023

with Lyons, Ben A., Christina Farhart, Michael P. Hall, John Kotcher, Matthew Levendusky, Joanne M. Miller, Brendan Nyhan, Kaitlin T. Raimi, Jason Reifler, Kyle L. Saunders, & Xiaoquan Zhao

Journal of Experimental Political Science, 9, 225-240.

Psychological attachment to political parties can bias people’s attitudes, beliefs, and group evaluations. Studies from psychology suggest that self-affirmation theory may ameliorate this problem in the domain of politics on a variety of outcome measures. We report a series of studies conducted by separate research teams that examine whether a self-affirmation intervention affects a variety of outcomes, including political or policy attitudes, factual beliefs, conspiracy beliefs, affective polarization, and evaluations of news sources. The different research teams use a variety of self-affirmation interventions, research designs, and outcomes. Despite these differences, the research teams consistently find that self-affirmation treatments have little effect. These findings suggest considerable caution is warranted for researchers who wish to apply the self-affirmation framework to studies that investigate political attitudes and beliefs. By presenting the “null results” of separate research teams, we hope to spark a discussion about whether and how the self-affirmation paradigm should be applied to political topics.

Link